Raffael Dedo Gadebusch

LAL-RED IN HONOUR OF KALI

Since the 2000 reopening of the Museum of Indian Art in Dahlem, the modern and contemporary art of the subcontinent no longer receives second billing in Berlin. Museum visitors have encountered representatives, both older and recent, from the Cholamandal Artists Village in Tamil Nadu as well as the Chandigarh visual artist Diwan Manna and the photographer Dayanita Singh. The remarkable response to the exhibitions at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum, organized together with the Neue Nationalgalerie, has shown that the time has come for the national museums in Berlin to let the voice of contemporary India be heard.

Interest in India as a photographic subject has a long tradition, one which stands in close connection to the emergence of art photography. The curatorial activities of the museum will thus continue to place strong emphasis on this field.

Previous exhibitions have made clear that, while twentieth-century Indian art possesses regional identity, it can only be understood in dialogue with European modernity and postmodernity. This is demonstrated palpably by the paintings and graphics of the late Cholamandal artist Sultan Ali exhibited in Dahlem, which show clear references to Paul Klee; it is also found in the works of Ebenezer, which take their inspiration from the Italian Transavangardia, in particular Francesco Clemente.

The encounter between India and Europe is no doubt an important motive in the genesis of modern and contemporary Indian art. It must therefore function as the thread that runs through presentations of contemporary artists.

In the 175th anniversary year of the national museums in Berlin, the Museum of Indian Art has decided to feature works of Gabriele Heidecker. This is the first time that the work of a German artist has appeared in the museum's galleries. Large-format tableaux vivants-originally tarred basins filled with red liquid-and the resulting ‘skin' placed in glass interact with the permanent collection (fig. ), while photographs and a so-called ‘red lake'-an installation with liquid-have been housed in the museum's special exhibition space.

There are probably few contemporary German artists whose oeuvre deals so forcefully with Indian art. Some of Heidecker's works shown in this exhibition were themselves executed in India. As part of the 2001 ‘Festival of Germany in India', the Berlin artist exhibited her much-noticed Land Art Project ‘Red Lake Field' in New Delhi, which concerned itself with questions of Indian philosophy and religion (fig. ). Her photographs on display in the Museum of Indian Art show the metamorphosis of the lakes' red liquid as it solidifies under the Indian sun, from lightly dried surface to extreme craquelé.

Gabriele Heidecker's interest in India goes back to early childhood and remains a leitmotif in her numerous works today. ‘Lal - Red, in Honour of Kali' represents the quintessence, as it were, of this intensive encounter and preoccupation, which at times has taken on a kind of possession. Indeed, the beholder can hardly escape the presence of the artist's predominantly monochrome works.

Where do the roots of this obsession lie? When she was four, Heidecker spent a great deal of time playing in a room that housed the rest of her father's library, which had been salvaged from the rubble of Berlin and brought to southern Germany. Starting in the 1920s, the mysticism of India, its religious art and philosophy, became a central subject for German intellectuals-not least through the influence of the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore-and thus a natural part of any well-stocked private library. While the upper shelves held works from literature, history and philosophy, the lower shelves contained oversized art books, easily reachable for a child. Among those art books was a copy of Helmuth von Glasenapps 1928 Heilige Stätten Indiens, published in Munich by Karl Döhring. The black and white photographs of Indian sacred structures made a lasting impression on Heidecker (fig.). Pictures penetrating the depths of the subconscious as well as identification with the father who owned these ‘exotic' images may have played a role in the artist's discovery of India and her return to a distant childhood. In the 1970s, for the collective consciousness of those tired of reckless growth and in search of meaning, India became the home of spirituality. The first major trauma of the boundlessly-coddled Western World was Vietnam. The oil crisis in the early 1970s exposed the materialistic lunacy of a society based solely on expansion, so much so that younger people began to seek new forms of spirituality. In the mind of Heidecker's generation, India was the land of peaceful and spiritual living, the primal home of non-missionising religions, Gandhi's country. As a result, it became a veritable Shangri-la, the destination point of desire. Yet India was much more than that for the young student and artist. It was also the source of artistic inspiration par excellence, the land of colours that not only shone more brightly, but that were symbolically charged like nowhere else. The visual language of the Indian pantheon is endlessly diverse and of matchless creativity. Those less familiar with it find themselves transported to a foreign world full of new forms and colours. Emanations from bodies, figures with a multitude of heads, arms, and legs, stand for divine omnipotence and anticipate what today's genetic manipulation may make possible and what contemporary art impressively foils, as in the sculptures of Jake & Dinos Chapman. The concept of diversity appears to be Indian in origins. Behind all forms in India there is the spiritual, the metaphysical. Art is first and foremost religious; even in antiquity Indian art was highly abstract and-when needed to concentrate message and symbolism-very reduced. Śiva, perhaps the most powerful deity in the Hindu trinity, manifests himself in countless forms. His most important early manifestation is the Linga, an abstract phallus whose symbolism is much more diverse than traditionally understood in the West. The Linga does not stand for sexual potency or fertility, as supposed European parallels with the Greeks and Romans might suggest. Quite the contrary, it stands for the transformation of sexual energy into spiritual energy.

Earlier Linga representations in particular emphasize this aspect of Śiva, who is venerated as the great ascetic and lord of the Yoga (Yogeshwara). The Museum of Indian Art owns an interesting Linga from the second century CE, an abstracted phallus with a face of the deity (fig.).

A crucial experience in Gabriele Heidecker's life, and one of the most important sources of inspiration for her early work, was the 1972 ‘Tantra' exhibition in Stuttgart. After a successful showing at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1971, the exhibition came to Germany, where it created quite a stir. It presented cosmic representations and diagrams of Jainism and Hinduism, diverse Yantras and Rajput miniature paintings with artful renderings of tantric sexuality that would likely have both fascinated and irritated its viewers.

Ajit Mookerjee, the lender of the collection for the ‘Tantra' exhibition and the then-curator of the National Arts and Crafts Museum in New Delhi, triggered an avalanche. Going well beyond assembling a collection of tantric cult objects, Mookerjee's work created international awareness of tantric art's exceptional importance. Since then, Mookerjee has published various works shedding light on tantric representations and practices.

The reduction to archetypal symbols, a characteristic of Tantrism, strongly influenced Heidecker's understanding of art. Indeed, Indian art-as well as East Asian art and its early theoretical texts-show that abstraction was not a discovery of the twentieth century, much less of Europe. It was thus only logical that, after completing her studies in art and art history in Stuttgart, working as an art teacher, and having recently moved to Berlin, Heidecker would begin, in 1974, to study the history of Indian and East Asian art. It was also at this time that she decided to give up teaching and devote herself to freelance art.

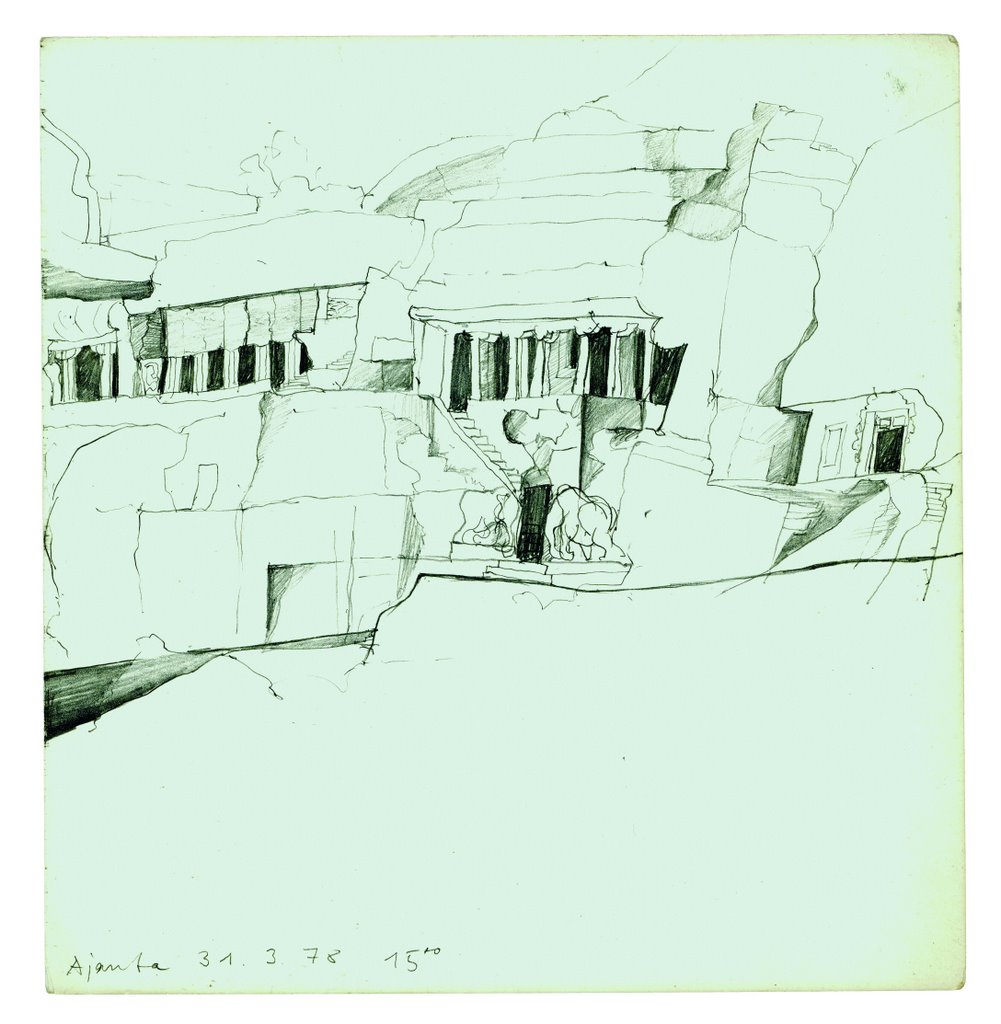

Heidecker's first prolonged trip to India in 1978 fulfilled a long-held wish. She travelled through large parts of the subcontinent, including Nepal and Sri Lanka. The island of Elephanta off Bombay, the monumental cave temples of Ajanta and Ellora, and the ghats of Benares left overwhelming impressions. She captured many stations of her journey in sensitive, yet powerful sketches (fig.). For the Berlin Institute of the History of Indian Art, she photographed the most important archaeological sites, work which allowed her to perceive her surroundings through the focus of the camera's lens. In Sri Lanka she experienced the intensity of nature, while in the North West, above all in Rajasthan, she encountered light and colour. At the Kanheri Caves north of Bombay, right at the start of her travels, she happened upon celebrations for Holi, the Hindu spring festival whose frolicking participants spray each other with colour. In the genre representations of later Indian miniature painting, the Holi festival was a favourite subject. This is documented by a late eighteenth-century miniature series in late provincial Mughal style that now belongs to the collection of the Museum of Indian Art (fig.).

Wearing as she was a summery white dress, Heidecker was not particularly keen to find herself among a large crowd. The experience was an initiation of sorts, one which provided her first sensual encounter with the colour red. The baptism by colour appears to have influenced her later work significantly. The colour red-‘lal' in Hindi-developed into a central theme in Heidecker's artistic engagement with India and is the focus of the exhibition ‘Lal-Red, in Honour of Kali'.

The thematics of red, in all of the colour's unfathomable depth and ambivalence, smouldered for years in the artist's subconscious. In 1991, as reaction to the conflict in Yugoslavia, Heidecker designed her ‘Red Line - October Installation'; in 1992, she created ‘Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité', her first rectangular work, which alluded to the massacre at Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

Yet the decisive spark that transformed the slow burning fire to a full-blown blaze didn't fly until 1993, during her first stay in Jerusalem. Both as a German in Israel and as a visitor to the old city who witnessed the ancient struggle between the major monotheistic religions, Heidecker was confronted with the theme of anguish. In Jerusalem she conceived of a ‘red lake' project, which she realized three years later as part of the installation ‘3x Memento in Jerusalem'. A series of ‘red lakes'-large tarred basins filled with a red liquid-followed. Six are now on display as red and black craquelés in the Museum of Indian Art.

In 2001 Heidecker achieved reconciliation with the colour red in her superb Land Art Project in New Delhi. All sorrow, all destruction has deeper meaning in the infinite cycle of rebirth. In Hinduism destruction is always a creative process, though graphic images in Hindu iconography with extraordinary depictions of blood ensure that destruction never becomes a mere abstract concept. Blood is often associated with death, but it is also a sign of life. From each drop of blood there emerges a new existence in the struggle with the demons. Kālī, or her emanation Chāmundā, who defends the cosmic order, drinks the blood of her victims. In a Sanskrit text, the Devīmāhātmya, written sometime during the fifth century CE, Kālī is described as the emanation of the goddess Durgā, as the personification of her wrath. When Durgā is threatened by the demons Chanda and Munda, Kālī springs from her brow. Kālī defeats them both and is given the name Chāmundā accordingly. In this form, she is represented as exceptionally savage: dancing in a wild rage, she tramples her opponents to death. After cutting off her victims' heads, she is fond of drinking their blood.

Hinduism understands Kālī's destructive work as a creative process. But it is also the demonic and destructive aspect of the black goddess that interests Heidecker. Her work is concerned with deep psychic trauma, latent societal violence, and the dark side of human nature.

The Museum of Indian Art owns one of the few complete miniature sets of a Devīmāhātmya manuscript from the end of the eighteenth century, which has neither been published nor exhibited in its entirety. The expressive and colourful miniature painting of the Pahari school depicts Kālī in battle against the demons (fig.). At the exhibition ‘Lal - Red, in Honour of Kali' individual pages will be on display for the first time in the new miniature cabinet.

As a natural extension of the dialogue with early art, museum visitors may visit the upstairs gallery, which houses hard-to-interpret tantric bronzes, an unusual Śivalinga from Nepal with four faces as well as important cult objects of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, such as a rare skull bowl (kapāla) made of rock crystal.

A large red craquelé from Heidecker has been placed near a Chāmundā cult stele from the eleventh century; in direct proximity is a monumental sculpture of Vishnu. The Chāmundā, which comes from central India, has been endowed with all the terrible attributes that constitute her destructive nature (fig. ). The work of Heidecker stands in dialogue with both the cult stele and the representation of Vishnu. The liquid has since dried, its surface-deep red and chapped-calls to mind clotted blood. Through its cracks, the black ground emerges. The large craquelé is the result of a metamorphosis, a natural process of drying and texturing, and it now stands, before the wall and in a black basin, as movement come to a standstill. Diagonally across from the work is Vishnu, his upright and static pose indicating his role as preserver of world order. He is the redeemer who appears again and again in new incarnations to restore cosmic balance (fig.).

By contrast, the destruction caused by Chāmundā is a precondition for new creation; it precedes preservation. The world must be recreated again and again; the old must be destroyed so the new can be created. It is a cycle that is best described by the cosmological form of a circle.

As in Tantric art, the circle is one of the essential forms of Heidecker's work. It manifests itself as the liquid is poured into the basin, creating concentrically expanding circles, or in the impressions left by the tubes. The tube stands for the Linga, an ‘instrument' for concentrating spiritual and creative energy; it also stands for the cosmic axis, the axis mundi, that plays a central role in Buddhist cosmology. The first work of Heidecker's in the exhibition, the ‘Black-Red Skin', can be understood as an overture. The red side of the ‘skin' has been intentionally placed facing away from a schematically reconstructed stupa, on whose walls hang Buddhist reliefs from Gandhara recounting Buddha's life. Visitors and devotees alike can walk clockwise around the stupa and ‘relive' the entire story of Buddha, from his birth to Parinirvana. Spatially, the cycle ends right where it begins; at the point where the circle closes, the visitor sees the black back of the ‘skin.' In the middle of the stupa, the most sacred of Buddhist structures, is an axis mundi. Unlike those normally found in stupas, this axis mundi has been made visible to the viewer.

The black and red skin is suspended in space, enclosed between two glass plates. It has been removed from the surface of one of the craquelés, the one side of the skin being red from the dried liquid, the other black from the tar. Its gate-like form and perforations where the tubes had once been allow the beholder to see in the direction of the stupa and the axis mundi (fig.). In this way, Heidecker's works engage not only with the objects in the museum's permanent collection; they also resonate with the architecture of the exhibition, which is based on the central cosmological forms of circle and square, from general plan to the smallest detail. The floor plan of the museum follows a cosmic diagram, a mandala, in whose centre is placed the inner sanctum-in this case a Buddhist sacred cave reconstructed to original dimensions. The idea of providing religiously-inspired art a corresponding space has seldom been accommodated in architecture with such painstaking care. Heidecker's works must be understood in connection with this ‘sacral' space. And, indeed, the special exhibition culminates in a cave-like installation, integrated in such a way so as to ensure a line of sight between it and the Buddhist sacred cave.

The creation of lines of sight, a basic principle of the museum's permanent collection, also informs the placement of Heidecker's works. Lines of sight allow better orientation and a stronger concentration on objects; they also establish connections between various cosmological ideas: the stupa and the cosmic axis, Kālī and Vishnu, the Buddhist sacred cave and the Hindu temple. Only through openness, juxtaposition, and combination can visitors apprehend the diversity of India's religions-as well as their commonality.

A room has been erected in the special exhibition hall, a kind of black box, which creates a separate space for museum visitors to encounter Heidecker's works (fig.) Within the black box one cannot escape them, for only a monochrome yet nuanced red glows from the darkness. In the middle of the box, there is a rectangular ‘red lake'. A black tube emerges from the centre of its red surface and black frame, at once Linga and axis mundi. A sacred space at multiple levels; it is a space that, in its simple layout, in its darkness, in the presence of a rectangular structure with Linga, recalls the interior of a Hindu temple. The devotee in the Hindu Temple seeks to achieve both concentration on the cult image through intensive viewing (darshan) and the resulting spiritual and sensual experience in the encounter with the deity.

Twenty-one photographs hang on the walls of the black box and document the metamorphosis of the solidifying liquid in the separate basins of the ‘Red Lake Field' in India. The stages of beauty, age, and decline recall the transience of everything material. Opposing the photographs is the Berlin ‘red lake'. It is located in a larger sacred space in the broadest sense of the word-the Museum of Indian Art.

While the exhibition was being installed, Heidecker poured and stirred the pigment mixture. Over the course of the ninety-four-day show, the mixture will solidify, creating a dialogue between the photographs from India and the Berlin installation, a dialogue that museum visitors can witness firsthand.

The meditative, almost religious experience that museum visitors claim to have when they engage with the sublimity of an art work that stands in harmony with the sublimity of the space that surrounds it is another subject of this exhibition. A twenty-first-century art museum may still be experienced as a temple for the beautiful and the sublime; yet it must also be a place where everything can be called into question. When the colour starts to crack, break apart, and burst into pieces, we are taken to a new dimension, one which reminds us that appearances are transient, illusory-that they, as Indian philosophy calls it, are Māyā. The major religions of India teach us that holding on is futile. This is the idea to which Gabriele Heidecker's work-the peeled red and black skins, the rough and split craquelés-gives haunting visual expression.

Raffael Dedo Gadebusch